For a show that seemingly enshrined objects of the recent past, its title- ‘ Flux’ was direct comment on today’s world by the artist, Nilesh Kinkale. The changing nature of the world we live in is informed by our choices of what we may call ‘ a better lifestyle’. The corollary is rather true : our reliance ( pun unintended ) on newer things is what leaves us with no choice but to switch from older, habitual to the unseen ways of life. Whilst the sheer novelty or ease of handling makes it imperative to use latest technologies and objects that flaunt it; we hardly ever bother about how our organic, aesthetic lifestyle is at stake. Of course, the new technology has to be put to work in place of the time- consuming, environment- unfriendly devices of the past , but have we taken a moment to see our past through those innumerable objects that we have done away with?

The 20-odd works in Nilesh Kinkale’s solo show that took place in Mumbai’s Jehangir Art Gallery provided many such moments, one at a time. Apart from the moments it facilitated, what was the show about? Was it about nostalgia? Was it a lament on a bygone aesthetic sense ? Did it romanticise the redundant ?

No, as the artist’s practice would tell us. Nilesh , from the days he attended Sir J J School of Art , had been painting & sculpting objects of everyday . His early influence was that of Prabhakar Barwe, as in case of countless students in JJ back in mid- 1990s . When Nilesh attended his Masters classes, it was evident that he was drawn more toward the structures of objects and more importantly, to the basic relationship of form to the object’s function. Nilesh’s table-fan with three ‘heads’ , a student-day sculpture now destroyed, was not only a mimesis of the oscillating function of the fan, but a quest to go beyond personification of an object, making inroads of abstraction in a given structure. The Bombay Abstractionists have long been on the scene, giving spiritual, poetic and sensuous dimensions mostly to abstract paintings, but Nilesh – like his predecesors Dilip Ranade and Madhav Imaratey, seemed to have avoided the easily available route. If this was Nilesh’s journey so far, it’s present manifestations looked stronger.

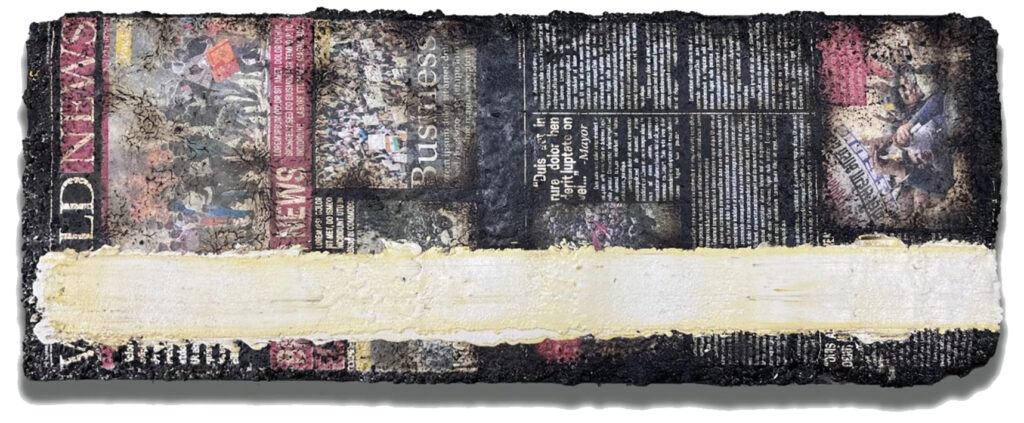

At the gallery, the frames were put on pedestals at various heights, with lights focused on each frame. The usual equations like frame- flatness, pedestal – sculpture were thus broken at the first sight, paving way for a closer look at Nilesh’s works that were neither flat nor sculptural. In the frames, there were objects of the recent past, treated for flattening to the maximum possible levels and then inundated in materials like cement, fiberglass or tar. They were objects like cameras, compass, alarm clock which have lost their existence to smartfones, as well as other objects like kerosene stove, wood-fired copper boiler for water, coal-operated iron for clothes that are now regarded as environment – unfriendly and fuel-inefficient. Brass , an alloy that made its presence felt from everyday kettles to the ceremonial trumpets, has lost it to plastic and steel. While Nilesh’s frames had all of them flattened, the title of each work reaffirmed the existence of the object by naming it. The identity of the objects was defaced and decreased, but the suggestive, subtle clues revealed it. Thus, while the flattened stove looked like any other flattened brass pot at the first instance, it’s stand and burner cried – this is not a pot. The cameras showed their distinctive fronts, the copper boiler retained its largeness, the brass kettle spoke out with its pout, the clock – though badly broken- invited a viewer to read between its tiny toothed wheels, the Bhopu horn kept its rubber part intact, and a the oil-measuring jug had not lost its triangularity.

Even as their three-dimensional existence was oblivious, the artist saw to it that the shapes do not get completely lost. This balance between destruction and abstraction was visible in each of the frames, and perhaps more so in a frame that had a typewriter. To use Prabhakar Barwe’s parlance , each frame had a pictorial and non-pictorial part ( ‘ chitra aani achitr ‘ in Marathi) . In Nilesh’s works, while the non-pictorial part was required to hold the object in a frame and various materials from fiber to cement to tar had to be used according to the weight of the object, it was also a site of artistic intervention. This intervention was not restricted to the colour-scheme or such mundane requirements, and went on to create a melancholy mood, to set a battleground for lost function and sustained form.

The museum-like display, the choice of objects, made an instant call to nostalgia which the artist may not have intended. However, while a viewer looked at each frame, Nilesh made his point clear: his abstraction here is not only about controlled destruction, but also about the rustic, rugged aesthetics of the forgotten existences.

Nilesh Kinkale, Live works in Mumbai Studio- 400 012

Text by Abhijeet Tamhane